Funny Stories and Droll Pictures

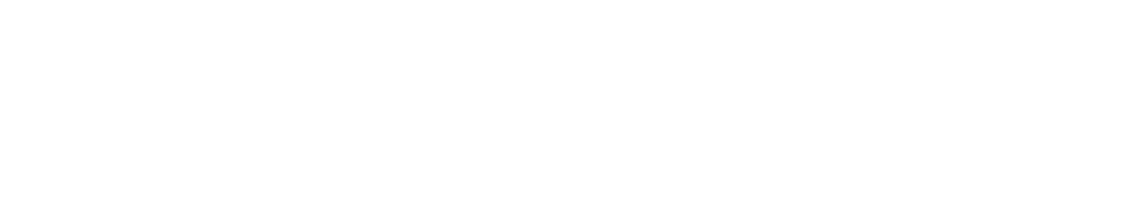

Heinrich Hoffmann was born in 1819 in Frankfurt on Main. His father was an architect and building inspector. Unfortunately, Hoffmann’s mother passed away when he was still a child. His father then married his late wife’s sister. Hoffmann’s childhood was not a happy one. Although he got along well with his stepmother, his father was a strict disciplinarian who expected him to behave well and perform his best in school. Hoffmann had to work hard to meet and maintain his father’s expectations.

In 1829, Hoffmann started studying medicine, again ‘motivated’ by his father. Between 1835 and 1846, the young man worked in a pauper’s clinic. From 1844 on, Hoffmann lectured students in anatomy at the Dr. Senckenbergischen Institute. In 1851, he graduated as a doctor and opened his practice in Frankfurt. To his luck, a doctor from a local mental asylum happened to retire. Hoffmann succeeded him as the new psychiatrist despite lacking experience with people with mental health conditions. But the job was far better paid, and he gained an extraordinary reputation for curing many of his patients. Well-respected in his city, Hoffmann published various essays about psychiatric topics and was an active member of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut, the Mozart Foundation, and the Freemasons' Lodge.

His statistical data showed that up to 40% of people with acute cases of schizophrenia were discharged after a few weeks or months and remained in remission for years, if not permanently. Hoffmann was doubtful that this was due to any therapy he may have given them. Hoffmann advocated for new, modern asylum buildings with gardens in the city’s green belt. His efforts were successful, and the new clinic was built at the site of today’s Frankfurt University’s Humanities campus.

Ha ha ha, or Ah Ah Ah?

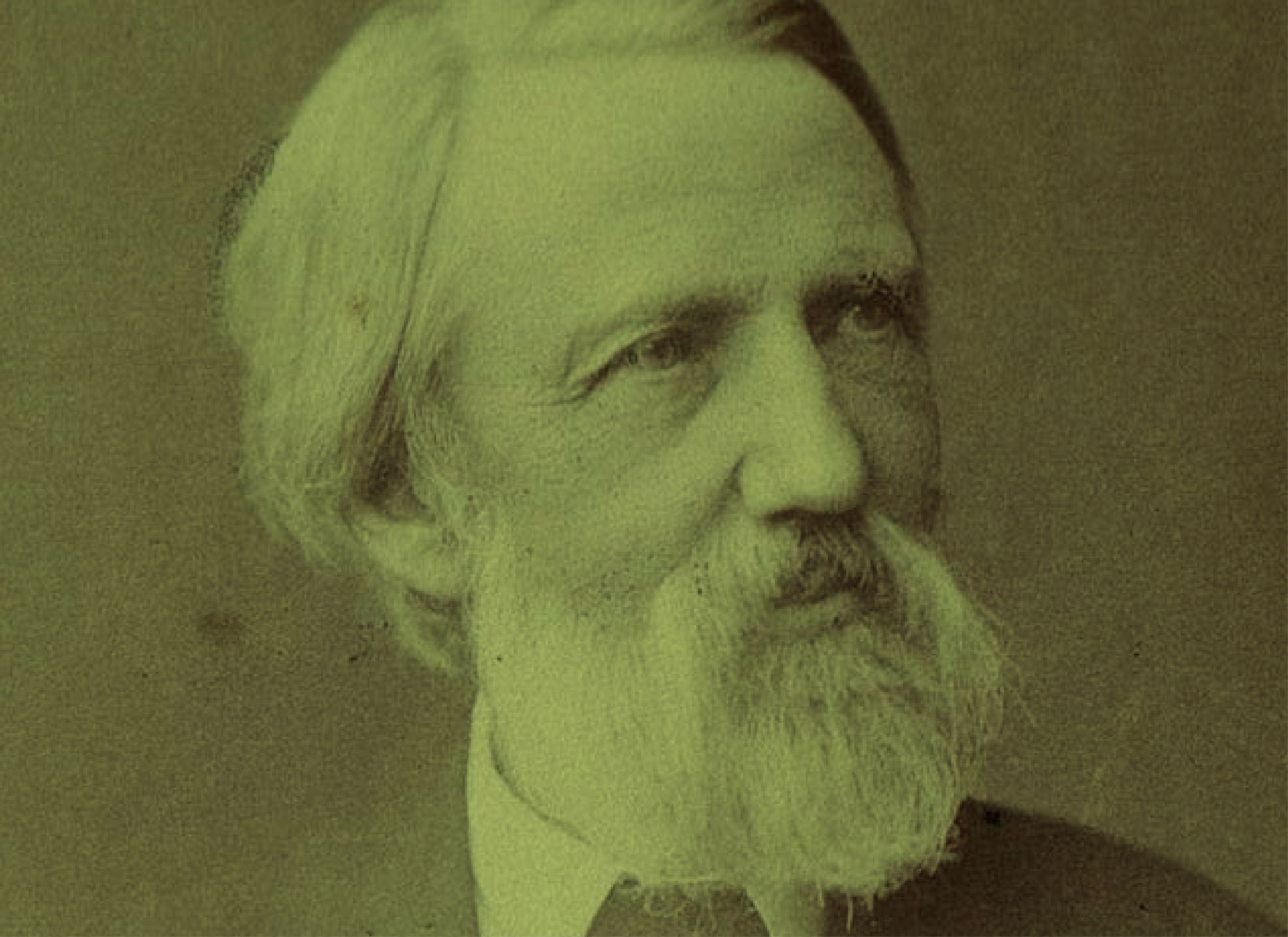

Hoffmann wrote the book that would later be titled Struwwelpeter in reaction to what he perceived as a lack of good books for children. Intending to buy a picture book as a Christmas present for his three-year-old son, Hoffmann instead wrote and illustrated his book. Hoffmann did not intend to publish the book when it was produced.

Hoffmann’s book was first introduced to the public at a meeting held by the Frankfurt literary club, the Tutti Fruti Society (Gesellschaft der Tutti-Frutti), on January 18, 1845. Zacharias Löwenthal, a co-founder of the publishing company Literarische Anstalt, purchased the book for 80 gulden during the event. This book may not have been published if it weren’t for Zacharias Löwenthal. He stumbled upon it and saw its unique value as a children’s book. Löwenthal urged Hoffmann to publish it, but Hoffmann had reservations. He feared publishing a children’s book could harm his reputation as a doctor and poet. Finally, with some encouragement and a “bright, wine-influenced whim,” Hoffmann agreed to publish it under the pseudonym “Reimerich Kinderlieb” in the first edition. Hoffmann later wrote that “that night, at 11 o’clock, I had, almost without knowing what I had done, suddenly become an author of juvenile books.”

Hoffmann had already published poems and a satirical comedy before publishing his famous collection of illustrated children’s verses, Struwwelpeter, in 1845. The book was a hit and had to be regularly reprinted, with numerous foreign translations. Despite its anti-heroes, Hoffmann’s contemporaries did not consider the book cruel or overly moral. The original title, Funny Stories and droll pictures, suggests that Hoffmann intended to entertain.

Following the success of Struwwelpeter, Hoffmann continued to write children’s books, but they were less popular than Struwwelpeter. He also wrote satires and humorous poems for adults, often showing his skepticism toward ideology and his dislike for religious, philosophical, or political bigotry. He participated in the Vorparlament and joined the Freemasons but later left due to their refusal to admit Jews.

Struwwelpeter Legacy

Struwwelpeter was revolutionary for its innovative approach of arranging the text around the images, making it a popular picture book and an inspiration and beginning to comics. The book was foundational for writers and illustrators such as Edward Gorey, Roald Dahl, Maurice Sendak, and Dick Bruna. Struwwelpeter was also one of the first publications to make use of chromolithography. It has since been translated into numerous languages and editions. It even inspired adaptations such as operas and films like Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands, which took inspiration from the Struwwelpeter’s unruly hair and the Scissorman’s act of cutting off a child’s thumbs to create the gentle yet tragic character of Edward Scissorhands in his 1991 film.

Struwwelpeter meets modern society

The stories feature such characters as the title character, a boy whose untamed appearance is matched by his naughty behaviour; a child who plays with matches and is burned to ashes; and a tailor who cuts off the thumbs of children who suck them. The tales in the collection are by some lights amusing and harmless and by others excessively gruesome and frightening.

— Britannica

In the early 19th century, attitudes changed as Struwwelpeter was criticized for its outdated approach to “disobedient” behavior and grotesque ‘educational’ methods. Educators believe the stories and images are too disturbing for children’s entertainment. However, children have been told violent and scary stories throughout history in fables and fairytales. Dr. Hoffmann’s strict upbringing may have influenced the content, but some researchers suggest Hoffmann intended it to be satirical.

Hoffmann’s Work

More articles

Atlas Obscura: Struwwelpeter Illustrations

KQED: How One Brutal Children’s Book from 1845 Left Permanent Marks on Pop Culture

Thank you,

Caleb