William Blake: Visionary for the Modern Picture Book.

Depending on who you ask or where you search, getting a clear answer on when the first picture book emerged is tricky. Is it simply the first book for children, the first book for children that included text and illustration, or maybe it is the first instructional book for children, or something completely different?

And you who wish to represent by words the form of man and all the aspects of his membrification, relinquish that idea. For the more minutely you describe, the more you will confine the mind of the reader, and the more you will keep him from the knowledge of the thing described. And so it is necessary to draw and to describe.

— Leonardo da Vinci

Where do we begin?

Humans have been using pictures to tell stories for thousands of years. This can be traced back to the earliest cave paintings found in France and Spain, which could be up to 60,000 years old. It’s still being determined what these paintings meant at the time, but they were an essential form of communication. It is believed that the oldest known ‘illustrated book’ is an Egyptian papyrus roll dating back to around 1980 BC. Its survival, buried in sand, was likely due to pure chance, indicating that similar delicate artifacts may have existed earlier.

In the 15th century, printing made education accessible to more than just the affluent who had access to hand-crafted literature in the Western world. Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of movable type in the 1430s paved the way for successful mass publication in Europe. Some of the first books illustrated for children were chapbooks. These pocket-sized books were folded instead of stitched together and often contained simple woodcut pictures. Books during this time, before the 18th century, were not typically written solely for children, and their reading material was mainly for educational, religious, and moral purposes rather than entertainment. Illustrations in these books were minimal and usually consisted of small woodcut vignettes or engraved endpapers created by anonymous illustrators.

Still, some extraordinary books were published during the 15th to 17th centuries, establishing a foundation for future genres of children’s literature. The first example of a book with type and image printed together was Ulrich Boner’s Der Edelstein (The Precious Stone, 1461). Another foundational book was Les jeux et plaisirs de l’enfance (The Games and Pleasures of Childhood, 1657), dedicated to and produced for children. It stands out for its subject matter and the many engravings by artist Jacques Stella. However, the rigid postures of the children depicted in the engravings reflect the prevailing view of children as small adults.

John Amos Comenius’s Orbis Sensualium Pictus (The Visible World in Pictures, 1658) was a significant precursor in children’s literature. This comprehensive collection of captioned illustrations of the natural world is considered the first-ever picture book for children. Comenius was an educational reformer who recognized the fundamental differences between children and adults. The book was innovative and laid the foundation for the illustrated schoolbook. It remained popular in Europe for two centuries and was published in numerous languages and editions.

During the 17th century, the idea of childhood was changing. Children were no longer viewed as small adults or extensions of their parents but as individuals with distinct needs and limitations. Educators started advocating for children’s unique needs and accepting pleasure as a part of learning. The works of philosophers John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau were instrumental in this evolution of ideas. In 1693, Locke expressed in Some Thoughts Concerning Education that children should be treated as rational beings. They should not be prevented from being children, playing, or behaving as children. Still, they should be prevented from doing wrong. Rousseau viewed childhood as a pure and natural state, separate from adulthood. He believed that education should aim to preserve a child’s original nature, and teachers should see things from a child’s perspective. British educators were influenced by the writings of Locke and Rousseau, which ultimately led to a more compassionate approach to education that acknowledged the importance of enjoyment in learning.

As a result, children’s literature as we know it emerged as publishers across Europe started to produce books explicitly aimed at children. Although these texts still had an educational focus, the popularity of children’s literature, particularly illustrated books, increased. In 1744, John Newbery released an ABC book, A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, which is considered the first book created for children’s enjoyment. With advancements in paper and printing technology, the children’s book industry experienced significant growth throughout the 1800s.

William Blake reacted against this instructional children’s literature genre in the Songs of Innocence, taking the popular literary form and subverting it with the interdependency of text and image, and brought children’s books beyond just being an educational device.

So it comes about that the first masterpiece of English children’s literature, which is also the first great original picture book, stems from an impulse to integrate words and images within a single linear whole.

— Brian Alderson

William Blake’s Songs of Innocence exemplifies this shift to empathize with children and focus on their perspective. His peculiar visionary art style was completely new, not influenced by anything else in visual arts around that time. The significance of Songs of Innocence lies in its poetic exploration of childhood, the loss of innocence, and the underlying social critique Blake weaves throughout the collection. It continues to be celebrated as a literary work that delves into profound themes and offers insights into the human condition.

Who was William Blake?

He who binds to himself a joy

Does the winged life destroy

He who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in Eternity’s sunrise.

Eternity by William Blake

William Blake was born on November 28, 1757, in London’s Soho district, England. Though he briefly attended school, his mother primarily educated him at home. Blake was deeply influenced by the Bible from an early age, and it remained a lifelong source of inspiration, imbuing his life and works with intense spiritualism.

From a young age, Blake began having visions. His friend and journalist Henry Crabb Robinson recounted that when Blake was four years old, he saw God’s head appear in a window. He also reportedly saw the prophet Ezekiel under a tree and envisioned “a tree filled with angels.” At four years old, according to his wife Catherine, Blake first saw God. Peter Ackroyd reported that Biblical imagery ‘overawed’ him. He set out to share such visions when he became an engraver, artist, and poet. In a poem, he declared his goal was to “open the Eternal Worlds” and “open the immortal Eyes of man.”

During his youth, Blake showed a strong artistic talent. At age 10, he started attending Henry Pars' drawing school, where he practiced sketching the human figure by copying from plaster casts of ancient statues. He then went on to apprentice with an engraver at the age of 14, whose master was the engraver for the London Society of Antiquaries. Blake was later sent to Westminster Abbey to create drawings of tombs and monuments, which sparked his lifelong love for Gothic art.

Around the same time, Blake began collecting prints of artists who had fallen out of fashion, such as Durer, Raphael, and Michelangelo. Almost 40 years later, in the catalog for an exhibition of his work, Blake criticized artists who tried to create a style that went against the likes of Rafael, Mich. Angelo, and the Antique. He rejected the literary trends of the 18th century. Instead, he favored the works of Elizabethan writers like Shakespeare, Jonson, and Spenser, as well as ancient ballads.

Eternal Imagination

In the industrial age, few saw beyond the physical aspects of reality. Blake’s ‘Newton’ (1795-1805) captures this: Newton draws a circle on the seabed with his compass, focusing on what’s measurable. For Blake, this mentality trapped within the “epicycles of thought” induces “Single vision and Newton’s sleep.” Many of Blake’s contemporaries regarded him as eccentric or mad. But a different mood prevails today. Civilization itself can feel as if it teeters on the brink. Blake’s critique of ‘dark Satanic Mills’ now appears prophetic; his advocacy of the need for ‘Mental Fight’ to liberate the imagination sounds like a calling.

Blake believed the human imagination could reveal truths of existence, turning everyday experience into a revolution. He sought a ‘fourfold vision’ and claimed when he watched the sunrise, he saw an innumerable company of angelic hosts crying, “Holy, holy, holy.”

In William Blake’s perspective, imagination symbolized the foundation of the human spirit, a crucial element of our existence, and an endless wellspring of magnificence. According to Blake, the ability of imagination to surpass and alleviate the limitations of our nature could only be achieved through a connection with nobility and truth.

Aeon.co:What We Can Learn From Blakes Visionary Imagination

Faena.com: Letter from the Young William Blake

Faena.com: Imagination as the Pillar of Spirit

Redpepper.org: Streets of Imagination

Imaginative Works

So it comes about that the first masterpiece of English children’s literature, which is also the first great original picture book, stems from an impulse to integrate words and images within a single linear whole.

— Brian Alderson via Sing a Song for Sixpence.

Blake’s first collection, Poetical Sketches (1783), included verse protesting war and tyranny. In 1789 came his most famous works, Songs of Innocence, and in 1794 Songs of Experience. This collection of poems revolutionized children’s literature. Unlike the moralistic and preachy tales of the time, Blake’s poems celebrated the purity and joy of childhood. Through simple yet profound verses, he captured the essence of innocence, exploring themes such as imagination, playfulness, and the connection between humanity and nature. Both were printed with copper plates and finished by hand with watercolors.

Blake defied eighteenth-century conventions by favoring imagination over reason when creating his art. He associated with radical thinkers such as Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft and was against political and social tyranny. Blake’s works, including “The French Revolution,” “America, a Prophecy,” “Visions of the Daughters of Albion,” and “Europe, a Prophecy,” express this opposition. Additionally, he satirized the power of church and state in “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.” Blake believed that ideal forms should be created from inner vision rather than observation of nature. With The Book of Urizen, he explored theological tyranny.

1800 Blake moved to Felpham and taught himself Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and Italian. During this time, he experienced spiritual revelations guiding his work in the great visionary epics between 1804 and 1820—Milton, Vala, The Four Zoas, and Jerusalem. These works envisioned a new kind of innocence—the human spirit prevailing over reason.

Blake exhibited his art in 1808 and 1809, receiving mixed reviews from the public. His poetry gained recognition from a few notable writers but was not widely known. In his final years, he met young artist John Linnell who became a friend and helped to create new interest in Blake’s work. Linnell commissioned him to illustrate Dante’s Divine Comedy, which Blake worked on until he died in 1827.

Despite his brilliance, Blake’s work received limited recognition and financial success during his lifetime. He relied on the support of patrons and friends, including the Reverend John Trusler and the painter Thomas Butts, to sustain his artistic pursuits. Blake remained dedicated to his craft until his final days, producing an extensive body of work.

The Marginalian: William Blake vs the World

Today, William Blake is celebrated as a visionary and a pioneer whose profound insights into the human condition and spirituality continue to captivate and inspire. His illuminated books and poetry collections are cherished for their deep symbolism, imaginative depth, and intricate artistry. Blake’s legacy reminds us of the boundless possibilities of the human imagination and the enduring power of art to challenge conventions and provoke transformative thought.

BBC: William Blake the Visionary

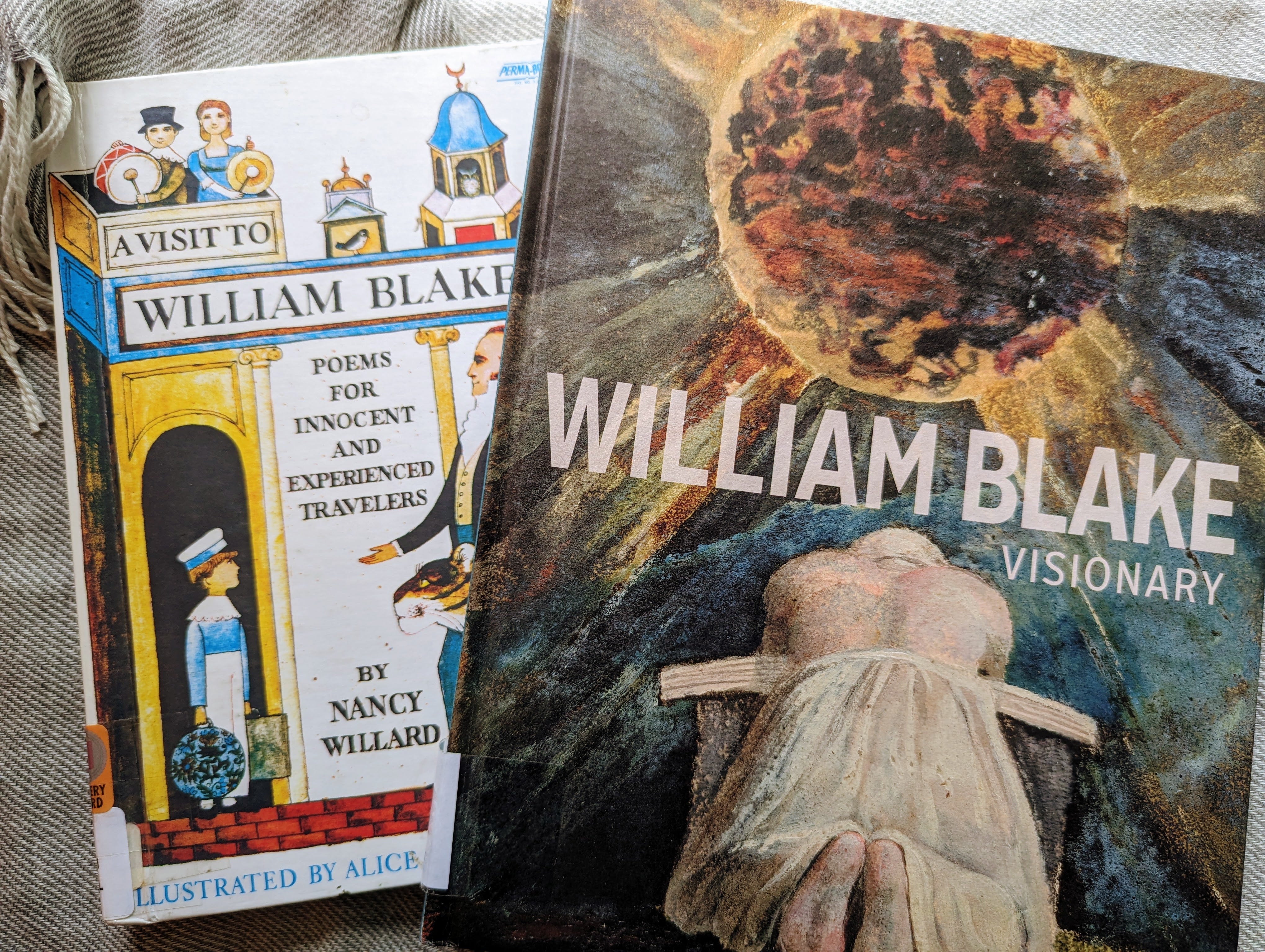

Blake’s Work

For my sanity and because I struggle with poetry, I will focus on “Songs of Innocence” and “Songs of Experience.” These two works are most noted as being children’s books' early sources.

A link to the works discussed to follow along.

More of Blake’s works can be found here.

1789: “Songs of Innocence.”

The Songs of Innocence depict the simple dreams and worries that shape a child’s life and show how they change as they grow up. Some poems are from a child’s point of view, while others describe children from an adult perspective. Many poems highlight the positive aspects of natural human understanding before it is tainted by negative experiences and adulthood. The artwork, or scans of the artwork, are stunning. Blake does a great job of using his work to tell a story beyond the text, which creates a beautiful back-and-forth.

Notable and favorites from the series of poems, “Introduction”, “The Lamb”, “The Chimney-Sweeper”, and “Spring”.

“Introduction” does an incredible job of setting up the poems we are about to read and sets the tone from the start while allowing some surprises to be discovered as we read beyond. “The Chimney-Sweeper” is my favorite; it captures an indescribable feeling and experience. A lovely and subtly dark poem that I enjoyed.

1794: “Songs of Experience.”

The Songs of Experience poems explore the idea that the harsh realities of adulthood can destroy the goodness of innocence. They use parallels and contrasts to illustrate the weaknesses of an innocent perspective, such as in “The Tiger” where opposing forces in the universe are addressed. Sexual morality is also discussed, specifically the harmful effects of jealousy, shame, and secrecy on innocent love. Experience adds a layer of darkness to the hopeful vision of innocence but compensates for its blindness.

Notable and favorites from the series of poems, “The Sick Rose”, “The Fly”, and “The Tiger”.

These three poems are engaging and thought-provoking. The pair’s images evoke a cheerfulness that contrasts some of the subtle darkness from the poems and their reality of life, death, bad things happening, and coming to terms with it all—a lovely balance between text and image.

More articles on William Blake

JSTOR: William Blake Radical Abolitionist

NY Times: William Blake vs the World

CemetryClub: Tombstone for a long Neglected Grave

Thank you,

Caleb