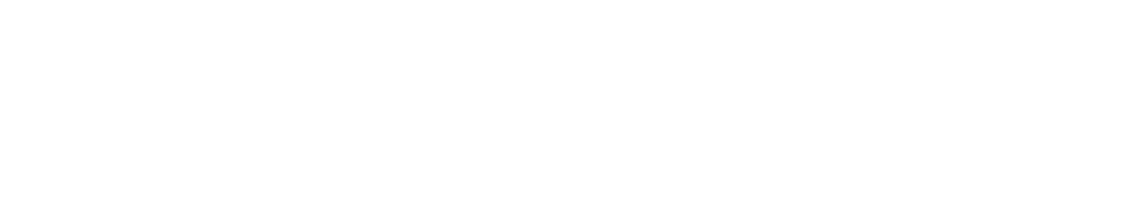

Alois Senefelder - Experimental Discovery

In the late 18th century, a Bavarian playwright named Alois Senefelder accidentally discovered lithography, duplicating scripts by writing with greasy crayons on limestone slabs and then printing with rolled-on ink. The limestone retained the crayon marks, allowing for almost unlimited printing. Eventually, in the early 1900s, color was incorporated into this process; thus, Chromolithography was born.

At the time Chromolithography, quickly found a variety of uses in art and commerce. Portraitists, illustrators, and famous press artists embraced lithography and chromolithography as a means of multiplying drawings. Many of the era’s most significant artists used it as a tool for graphic invention, leading to a boom in picture book design and cultural impact as the likes of Edward Lear, Heinrich Hoffmann, and Randolph Caldecott utilized the new processes with the old to usher in what we know as the modern picture book.

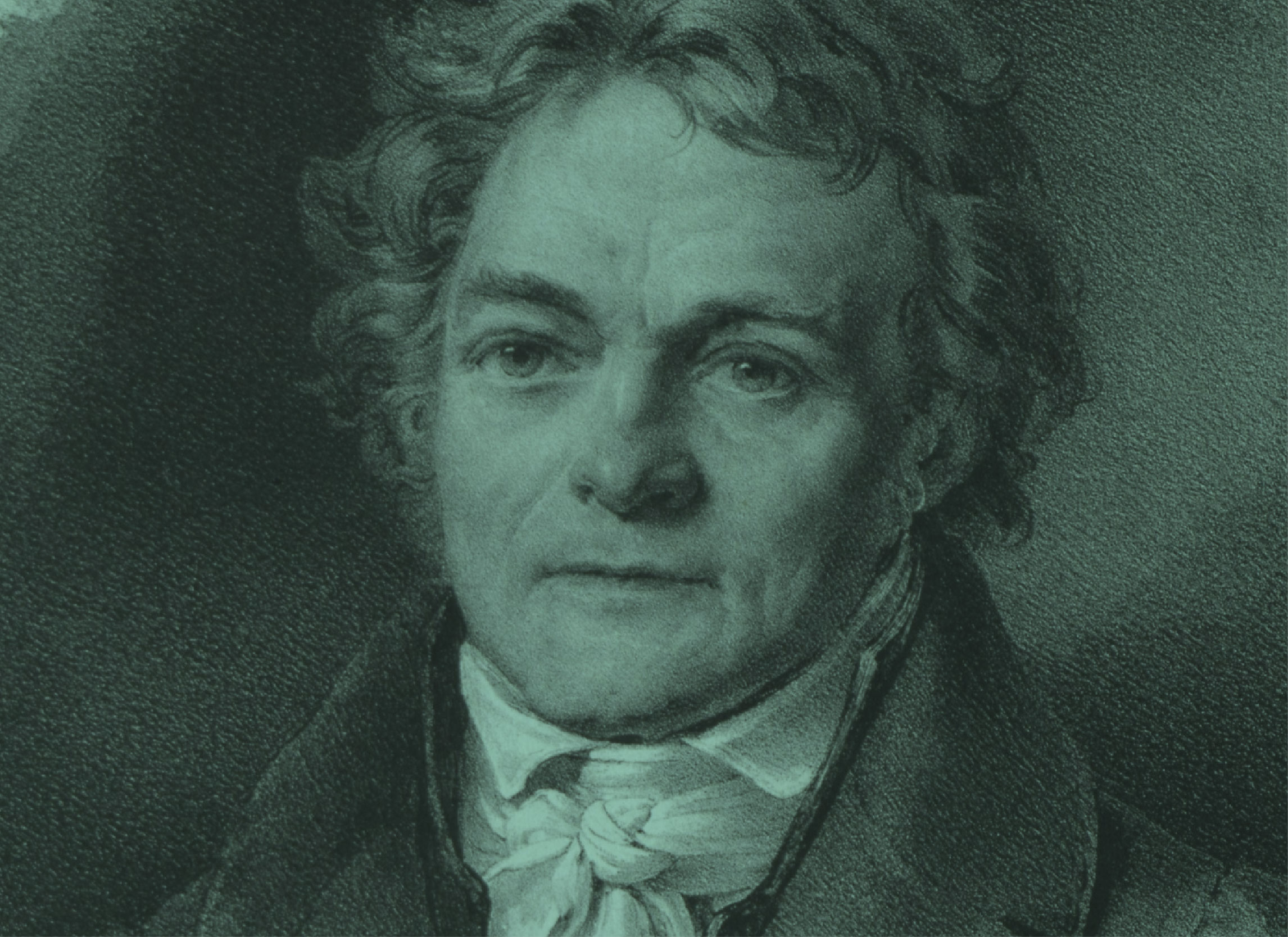

George Baxter - Color Print Innovation

In print, color was typically added by hand before the 1830s, but printing color from woodblocks was later developed independently by George Baxter and Charles Knight. During the late 1830s, numerous experiments were conducted in color printing, including Baxter’s. However, these experiments were carried out under different circumstances and in various parts of Europe, making it difficult to account for them. It is believed that they were a delayed response to the mechanization of printing, which was beginning to take effect throughout Europe. The introduction of paper-making machines and powered printing machines for letterpress printing in the early nineteenth century paved the way for the industrialization of printing, creating larger markets for its products. As a result, the hand coloring of prints became outdated. Additionally, Michel-Eugène Chevreul’s influential work on color theory, De la loi de contraste simultané de couleur, which was first published in Paris in 1839 after a series of influential public lectures, had an impact on various trades and occupations, not just in France.

Between 1835 and 1840, several prominent lithographers experimented with color. Frédéric Simon in Strasbourg and Charles Hullmandel, Owen Jones, Day & Haghe in London were among the leaders in this field. Meanwhile, relief printers such as Charles Knight, Gustave Silbermann, and Didot frères also printed in color during this period. Hullmandel even produced four double-spread color lithographs after wall paintings for Hoskins’s Travels in Ethiopia before Baxter applied for his patent in 1835. Although Frédéric Simon printed the first of a series of Jean Midolle’s calligraphic specimens in color between 1834 and 1835, Baxter is credited with being one of the first to produce color lithographs. Knight and Hullmandel later made pictorial chromolithographs in 1838 and 1839, while the others focused on decorative work.

Baxter’s method consisted of a steel key plate outlining the intricate details and shading necessary for a fully finished monochrome print. He then applied up to 20 blocks made from wood, copper, or zinc, one for each color, to achieve the final product. Aligning each block perfectly was a significant challenge, but the process proved commercially viable and was the first successful method of color printing. Despite its complexity and lack of modern labor-saving technology, it was a significant achievement for its time. Baxter prints are identifiable by the characteristics of each technique involved in the process; the aquatint grain, the darker lines of the intaglio plate, and the squashed rims of the relief blocks.

Baxter’s innovative process received a royal patent in 1835 (Patent No. 6916 – Improvements in Producing Coloured Steel Plate, Copper Plate, and Other Impressions). The patent lasted from 1835 to 1854. During the last few years of this period, Baxter licensed his method to various printers, who used it until the 1870s.

Despite his technical excellence and the general popularity of his prints, Baxter’s business was never profitable. This was due to his laborious process and perfectionism, which caused him to miss many commission deadlines. Baxter was declared bankrupt in 1865 and died in 1867 after an accident involving a horse omnibus. It is estimated that he printed over twenty million prints during his career.

History of Info: First Viable Method of Color Print

History of Info: Mass Market Printed Color Plates

George Baxter: Chromolithographic

Charles Knight - Publishing

Author and publisher. Although he only received a few years of formal education, he gained extensive knowledge about books through his apprenticeship with his father, a bookseller and printer. As a publisher, he produced a variety of serials and information compilations that included illustrations aimed at making affordable reading material more accessible to the general public.

In March 1828, Charles Knight and Henry Brougham joined forces to establish the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Knight took on the role of publisher, and during the following years, he produced several publications such as the Quarterly Journal of Education (1831-36), Penny Magazine (1832-45), and Penny Cyclopedia (1833-44). The Society also introduced innovative publishing methods, such as releasing The Pictorial Bible (1836), The Pictorial History of England (1837), Pictorial Shakespeare (1838), and Biographical Dictionary (1846) in serialized parts.

The Penny Magazine, the thing Knight is most well known for, was released on March 31, 1832. It was a weekly newspaper consisting of 16 pages, printed on both sides of a large sheet of paper and then folded. The publisher and writer, Charles Knight, created the magazine on behalf of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. The magazine’s unique features included its low price, various topics, and detailed woodcut illustrations. The magazine’s circulation was also a novelty, with 200,000 copies distributed quickly. This was a remarkable feat for 1832, as it would have been impossible to print that many copies a mere five years prior. However, introducing flat-bed presses that could print over 4000 sheets per hour made The Penny Magazine possible.

The Penny Magazine was published every Saturday to entertain and educate the working and lower-middle classes. The choice of publication day was intentional, as those in the working class often had little time for leisure activities during the workweek. Knight wrote most of the content, and illustrations were included to accommodate readers who could not read. However, woodcuts were expensive, so a high circulation was necessary to cover printing costs. As a weekly publication, it did not focus on current events but provided information on literature, arts, entertainment, and science to enlighten its audience.

According to author Richard Altrick in 1957, Knight put in much effort and money to acquire quality woodcuts. He purposely emphasized pictures to attract the attention of people not used to reading. Even those who couldn’t read found Penny Magazine’s illustrations enjoyable and worth their penny. Many buyers remembered the magazine fondly because of the illustrations, perhaps more so than the actual text.

After finishing with the Society, Knight continued to pursue his interest in pictorial part-works. He published various titles, including The Land We Live In, Local Government Chronicle (1855), and Popular History of England (1856-62), in eight volumes. Additionally, he authored a biography of William Caxton and works by renowned writers. Although he retired as a publisher in 1864, he continued writing until his death in 1873. One of his notable publications was his autobiography ‘Passages of a Working Life During Half a Century.’

Charles Knight was a remarkable person who helped to make a monumental contribution to publishing inexpensive literature and was an influential author.

Linda Hall: Charles Knight Publisher

Thank you,

Caleb